From Mav: A couple weeks ago, our good friend Matthew Brake of Pop Culture & Theology, posted about appearing on another podcast about deconstructing comics. Matt was really just pimping his discussion on that show talking about Animal Man (which is a good conversation and you should listen), but it got me to thinking about the idea of “deconstructing comics” or what it is people mean when they say it. Way back when the movie Batman v. Superman came out (which I pretty much HATED… go ahead… at me!!!) I started hearing the people who were fans of it talking about the way it “deconstructed” comics. In fact, after a lot of the criticism, I heard an interview with Zack and Deborah Snyder where they addressed the negative criticism and said something like “after the movie what we learned is that a lot of people don’t like having their superheroes deconstructed.” Zack Snyder has repeated this stance any time anyone has criticized one of his DC movies and it has been a lead up to his fabled “Snyder Cut” of the Justice League movie. And each time I hear him say it, something has become more and more clear to me: Zack Snyder doesn’t actually know what “deconstruction” means.

He’s not the only one. I hear comic book people (and let’s face it, I mostly mean superhero fans) say the same thing about stuff like Joker, the Dark Knight Returns and Nolan’s Batman films, the Kick-ass comics and films, and both comic and film versions of Watchmen (including, once again from Snyder, the director). And honestly, those are actually all fair to one extent or another. But I’ve also seen it argued about everything that came from early Image Comics books (McFarlane’s Spawn, Lee’s WildCATs, Liefeld’s Youngblood, etc.) and any number of similar “gritty” books and there I very much disagree. Mostly, it seems, people think that “deconstruction” means “really violent with some swearing… and maybe if you’re lucky you see a female nipple or two.” That’s not what it means. However, it’s not surprising that people use it that way. The concept is misunderstood even by writers and sometimes critics. It’s definitely misunderstood by comic fans. I blame Watchmen.

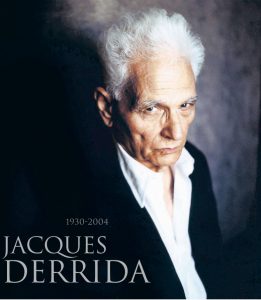

The term “deconstruction” comes from Jacques Derrida and it refers to the critical evaluation of literature by breaking the form apart from the meaning. The basic idea of a deconstructionist text is to tear apart the format, style, language and tropes of a genre and see what the actual meaning is. In doing so, you can comment on the ideology and politics of the genre. You can find its faults. You can explore the culture surrounding its production. In short, deconstruction is about… well, THIS SHOW. And honestly, that’s what Watchmen did. One thing people, including Snyder, believe about Watchmen is that it postulates that a world where superheroes exist would inevitably be hyper violent. in fact, Snyder’s counterargument against his critics is always “if you think that a world where superheroes exist wouldn’t be fascist, you’re nuts.” And honestly, that’s sorta kinda him getting deconstruction. He’s trying to show that superheroes are innately fascist. And that’s one possible take. But his equivalence of fascism to simply causing as much wanton destruction is reductive. Because he misunderstood Alan Moore’s Watchmen. For one thing… it’s really not that violent. In fact, actual depictions of violence in the original text are extremely rare and brief, almost as though Moore and Gibbons were bored by them. But the fans weren’t. The “gritty realism” of Watchmen is what a lot of people gravitated towards. So the very tropes that Moore and Gibbons were trying to comment on, is what they inadvertently ended up perpetuating by causing so many people to copy them on a surface uncritical level. In the 1990s, superhero comics became a contest to see who could have the bulkiest dudes or the sexiest chicks use the biggest guns to kill the most people within twenty-two pages.

Except that focus on hyper violence ignores all the other deconstruction that was going on. This returns us to Grant Morrison’s Animal Man as well as his work on titles like Doom Patrol and The Invisibles and other Moore texts like Swamp Thing and Miracle Man or later books like Warren Ellis’s Planetary and The Authority. Many of them ventured into postmodernism as well by questioning the very meaning of narrative. Animal Man is again very relevant here, and I’d add the string of books from 90s where characters were aware of the comicbookness and explored fourth wall breaking or metatextual and intertextual stories, like John Byrne’s She-Hulk, Dave Sim’s Cerebus, or Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. Oddly enough, I’d say the most popular modern characters that best exhibit actual deconstruction (and postmodernism) even through hyper violence are probably Deadpool and Harley Quinn. Though my personal favorites are easily going to be Tom King’s work on Vision, Mr. Miracle, and Batman, and if we’re allowed to venture outside of the world of superheroes, Steve Pugh’s recent Flintstones revival, Mark Russell’s Snagglepuss Chronicles and the best show on television, Riverdale (and yes, I’m really serious here, and it’s relevant).

But what a lot of this misses is the idea of reconstruction. If there are comics that tear the medium apart to find its faults and comment on the society in which they are created, then we should perhaps look to the stories that are actually trying to piece the genre back together to create something that can be aspirational to the contemporary reader. Kurt Busiek’s Astro City is probably the most well known example here, but Moore and Morrison have tried to do this as well with stuff like America’s Best Comics and All-Star Superman. I would also include Robert Kirkman’s work on Invincible, Matt Fraction’s Hawkeye, Chelsea Cain’s Mockingbird and I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the work of (friend of the show) A. David Lewis on Kismet, Man of Fate.

So that’s what we want to talk about. What does “deconstruction” mean to you in the world of comics and comics related media? What about “reconstruction”? What works and doesn’t work? What other examples should we talk about?

From Wayne: I’ve been hearing about the Deconstruction of the superhero since somewhere in the early ’80s. Watchmen and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns were the ones that got the most attention at the time, but it didn’t start there. A lot of the comics that came out of the early days of the Direct Market were taking the standard tropes of the genre and attempting to do things that would never be allowed in the hallowed halls of Marvel and DC. Books like Nexus, Grimjack, DNAgents, Coyote, and many others were looking at superheroes through a new lens. I would even make the argument that this was happening in more subtle ways in the mainstream with books like the Wolverine miniseries and the Miller run on Daredevil. Postmodern, maybe, but certainly they were presenting the reader with ideas that felt new to us at the time.

As Mav said, somewhere along the line it stops being a deconstruction and simply becomes the new cliche. I’m not sure Image was a deconstruction of the genre so much as a continuation of a new set of tropes without the insight or commentary that others provided (though I will give you that Image was a deconstruction of creator’s rights up to that point).

Animal Man was not just a deconstruction of the superhero genre, but also offered a critique of the much vaunted notion of continuity. It wrestled with the ideas of reboots and retcons as part of the meta-narrative of comic book history.

I’m interested in the idea of reconstruction as well. After you’ve knocked something down what do you replace it with? I’m also convinced that both de and re construction take place simultaneously. While Watchmen and Dark Knight were were crumbling the foundations of what superheroes had always been, series like Mage, Zot!, and even Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, were presenting new visions of what superheroes can be. Planetary and The Authority were responding to the Image Age and simultaneously broke it down to show the cracks while creating the next phase of the genre that would need to be questioned.

I think these ideas can be applied to the larger world of comics publishing as well, in terms of changes in ways of publishing, creator’s rights, distribution, and format, but maybe that’s a different show.

From Wayne – Addendum: Just since writing the above I read the latest iteration of Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt by Kieron Gillen and Caspar Wijingaard, which deals overtly with all of the issues we’re talking about here, and now I have a lot more to think about before we record. Gillen’s series Once and Future is doing the same thing with Arthurian legend, now that I think about it.

What is the role of nostalgia in reconstruction?

John Darowski that’s a great question!

John Darowski addressed this a little bit I think