From Mav (with Matt Linton): We’ve talked a lot on our show about Laura Mulvey’s theory of the “the male gaze”. In short, the male gaze describes the tendency of narratives to position female characters primarily as objects of desire to be consumed by male protagonists and readers. It argues that regardless of the reader’s personal sexual identity, the narrative often positions the reader to interact with the story as a straight male. Most importantly, it surmises a female character whose job is “to be looked at”. Being attractive to the audience is her main role before anything else. We’ve talked about how people tend to misuse the term and the theory and we’ve talked about how the theory has been extended to other “gazes” in the decades since Mulvey first offered the argument. Probably most notable are “the female gaze” and “the queer gaze”, which people use to varying degrees of association with Mulvey’s original term, or to simply discuss the idea of sexual presentation targeted at a presumed demographic (it’s more complicated than that and we’re actually going to do an introduction to the male gaze show before this one). But there are others and in fact I’m even a little guilty of doing this myself; I theorized “the kid gaze” back when we were talking about sexy cartoon characters. However, a couple weeks ago on my other podcast, GoshGollyWow, our guest Matt Linton proposed a new one, “the fanboy gaze” and I’ve been dwelling on it ever since.

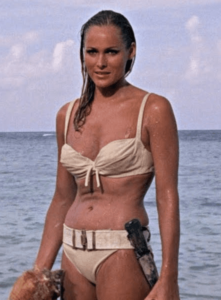

In short, Matt’s argument is that the fanboy gaze differs from the classic male gaze in that we, as the consumers of a text, are positioned to lust after a more active protagonist who is not necessarily an obvious sexualized object but also to specifically identify with that character. The classic male gaze character, at least in action genres, is a damsel-in-distress. Sex appeal is more important than any other trait. In many cases, especially with the contemporary action movie (and comics), the standard male gaze is extended beyond Mulvey’s original idea to allow for active female characters who still function as visually fetishized sexual objects. A lot of my dissertation work extends the argument of film theorist Cristina Lucia Stasia who argues that female action heroes are allowed to be violent and non-passive only if they are otherwise conventionally heterosexually attractive. That is to say that women can be badasses if they’re hot enough. If I understand Matt enough (and we’re going to have him on the show to explain it himself), he’s arguing that you can substitute conventional geek tropes for conventional sexual attractiveness, but then functionally you simply end up creating an alternative model of patriarchal attractiveness that does the same thing. Lusting after a character because she’s brainy or geeky or punky or a deadly fighter or any other trope isn’t fundamentally different than lusting after her because of her boobs.

Matt’s standard example here is Kitty Pryde in the X-Men comics. Kitty differs from other female characters in the X-men orbit in that she is not typically hypersexualized. She’s not overly buxom. She doesn’t wear revealing costumes nor stand or fight in pornographic poses. At least not usually. Instead she is presented as something of a girl-next-door. She’s often a tomboy. She’s very much “one of the guys” and “cool.” But she’s still a character that is designed for the (straight male) reader to fall in love with. Only, she gives an excuse for the reader to feel a sense of enlightenment for being “not normative” despite essentially fulfilling the same role as Stasia’s version of the male gaze. It somehow feels more enlightened and less chauvinistic to like the girl who isn’t the stereotypical sex symbol. Furthermore, Matt notes that Kitty and other Fanboy gaze characters are typically the Point-of-View characters for their narratives. Kitty for instance, as a 13yo girl when she was introduced in 1980, was clearly designed to be a reader surrogate for the presumed teen reader demographic, even though that standard reader was presumptively male.

In this way, Matt compares Kitty to Robin… or the Robins. Ever since Dick Grayson first appeared in 1940, the role of Robin has served to give a more identifiable touchstone to welcome the reader into Batman’s world. Typically this role is male, but Robin is almost always more excited to enter the world of superheroes than the Batman he is attached to. For Batman, adventuring is at best a responsibility and at worst a burden. But Robin, essentially being a Batman fanboy himself even in that first appearance in Detective Comics #38, knows that being a superhero is a privilege. Therefore the reader can delight at his presence. There’s an implicit attempt to encourage the reader (regardless of gender) to identify with the Robin. The same is true of similar teen POV insert characters like Bucky, Speedy, Kid Flash, or any other Teen Titan (the golden and silver age of comics were full of them). For female readers, this means that they are expected to adopt a queer identity when reading the book or to identify with the female exhibitionist characters. This is standard for Mulvey’s male gaze concept. But Matt suggests that the fanboy gaze complicates this by often offering a female POV character, like Kitty, Jubilee, or any of the female Robins, that the presumed male reader is supposed to both lust after and identify with. Thus, the fanboy gaze becomes presumptively queer in and of itself. If the male gaze assumes a heteronormative male identification as both the audience member and as the diegetic viewer of the object of the gaze, does the “fanboy gaze” have a similar dual-function of desire and identification?

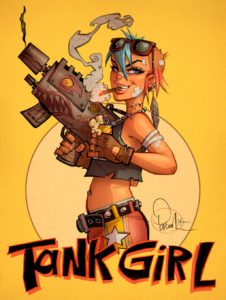

This probably gets even more complicated. I’m using teen sidekick characters just for simplification, but the fanboy gaze shouldn’t really require it, so much as simply requiring the presumptive male viewer to identify with the object of their lust. I think Buffy Summers and Katniss Everdeen fit very well in here and frankly any litany of manic pixie dream girls from throughout the history of media. I’d probably also add Lara Croft and any other video game character where you’re supposed to embody a sexy, but also brilliant, female character and pretend like the sexiness doesn’t really matter. Most of the time, I would argue, the distinctions that separate the fanboy gaze from the male gaze aren’t that drastic. However, they could be. I firmly believe that Tank Girl fits in this role as well. It doesn’t matter how counternormative she is, a key part of the character will always be “but she’s hot BECAUSE she’s counternormative!” And once you are selling that, then is there really a difference between what you’re doing and selling any sort of normative gaze?

I expect we can inevitably turn any discussion of the “Mary Sue” into a discussion of the Fanboy gaze as well. I’m starting to wonder if there’s a strong connection between the two. On one hand Kitty Pryde is still here, but I’d probably use the nigh perfect Hermione Granger here. Part of the Mulvey’s original problem with the male gaze was that it was effectively positioning the female viewer with only one possible outlet for association, that of a fetish object. The criticism Stasia makes is that applying agency only because the character excels at the fetishized quality is similarly limiting. I would argue that so called “Mary Sues” at least as a trope are effectively the same thing. Fetishization, in this sense need not be sexual. At the point in which you are expected to identify with a character simply because she is perfect, that’s not much different than lusting after her for the same reason. It doesn’t matter if the tropey perfection is brains or boobs, the effect would more or less be the same.

We want to know what you think. Is the fanboy gaze different than the male gaze and how so? Is it inherently queer? Do I, as a male reader, both desire AND want to be Kitty Pryde (or Tim Drake) and how does my own gender-identity and sexuality play into that? Can you think of other examples that add to this or complicate it? Give us your thoughts in the comments below.

My film school teacher told me she took a class years ago comparing the “male gaze” to the “female gaze”. And the example they used for the female gaze was Leni Riefenstahl’s TRIUMPH OF THE WILL. Showing how she framed the male Nazis in dominant low angles. I not sure that’s the best example. Haha