From Mav: Now this is going to be a very fun show. It’s time to talk about monsters! Obviously VoxPopcast is a geeky show. A lot of what we deal with is based on comic or video games or science fiction or fantasy. While these things are all very different, they have a common ancestor that sort of pervades the narrative of much of genre based fiction in any medium. The monster and the monster hunter! Whether we’re talking about the ancient text of Beowulf, the medieval Arthurian legends of Chrétien de Troyes or Edmund Spenser, 19th century’s Frankenstein or Dracula, or the 20th century’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer, we appear to be fascinated by the idea that there are beings of natural evil out there, and that it is the job of some noble and courageous hero to go and kill it. It’s an idea that is visible in the bible and in media as simple as the game of Pac-Man.

From Mav: Now this is going to be a very fun show. It’s time to talk about monsters! Obviously VoxPopcast is a geeky show. A lot of what we deal with is based on comic or video games or science fiction or fantasy. While these things are all very different, they have a common ancestor that sort of pervades the narrative of much of genre based fiction in any medium. The monster and the monster hunter! Whether we’re talking about the ancient text of Beowulf, the medieval Arthurian legends of Chrétien de Troyes or Edmund Spenser, 19th century’s Frankenstein or Dracula, or the 20th century’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer, we appear to be fascinated by the idea that there are beings of natural evil out there, and that it is the job of some noble and courageous hero to go and kill it. It’s an idea that is visible in the bible and in media as simple as the game of Pac-Man.

The idea of monster hunters facing monsters is kind of obvious. If conflict is the basic building block of fiction, then it make sense to have the basic story be an identifiable protagonist engaged in physical struggle with a clearly adversarial antagonist. It’s a story template that everyone can immediately get on board with. We don’t need to know the backstory for the original Pac-Man. We’re the good guy and there’s a bunch of ghosts running around. Ghosts are monsters. KILL EM! This is the basic plot of any number of video games in fact. Resident Evil has a very complicated backstory that pervades the entire game series and into the movies. I don’t actually know it. I don’t care. When I play the game at the arcade, I just know that if something is ugly it must be a monster. If it’s a monster, fucking shoot it in it’s fucking head! Good enough!

The idea of monster hunters facing monsters is kind of obvious. If conflict is the basic building block of fiction, then it make sense to have the basic story be an identifiable protagonist engaged in physical struggle with a clearly adversarial antagonist. It’s a story template that everyone can immediately get on board with. We don’t need to know the backstory for the original Pac-Man. We’re the good guy and there’s a bunch of ghosts running around. Ghosts are monsters. KILL EM! This is the basic plot of any number of video games in fact. Resident Evil has a very complicated backstory that pervades the entire game series and into the movies. I don’t actually know it. I don’t care. When I play the game at the arcade, I just know that if something is ugly it must be a monster. If it’s a monster, fucking shoot it in it’s fucking head! Good enough!

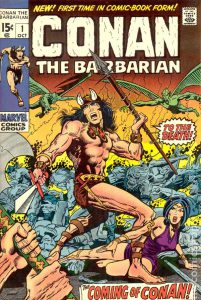

Of course complications can be layered on top of the base narrative of monster hunter vs monster to make it more interesting. Like I said, there totally is a backstory to Resident Evil. In fact, there’s even a backstory to Pac-Man. Conan the Barbarian stories are famous for this. At it’s essence Conan is basically just a big dude with a sword who kills stuff. Then more stuff comes at him and he kills that too. That’s it. That’s the narrative. An endless cycle of just killing whatever is in his way. But little tweaks to that basic template with simple subplots and rotating stock supporting characters have kept the character in continuous publication of some sort or another for 86 years. Keeping the base narrative relatable like this means that by tweaking the monsters and the settings slightly, we can map the monster hunter vs. monsters narrative as a allegory for any anxiety that the writers and readers might be struggling with from industrialization, to nuclear war, to the disease and famine, to financial crisis, to politics, to sexual frustration.

Of course complications can be layered on top of the base narrative of monster hunter vs monster to make it more interesting. Like I said, there totally is a backstory to Resident Evil. In fact, there’s even a backstory to Pac-Man. Conan the Barbarian stories are famous for this. At it’s essence Conan is basically just a big dude with a sword who kills stuff. Then more stuff comes at him and he kills that too. That’s it. That’s the narrative. An endless cycle of just killing whatever is in his way. But little tweaks to that basic template with simple subplots and rotating stock supporting characters have kept the character in continuous publication of some sort or another for 86 years. Keeping the base narrative relatable like this means that by tweaking the monsters and the settings slightly, we can map the monster hunter vs. monsters narrative as a allegory for any anxiety that the writers and readers might be struggling with from industrialization, to nuclear war, to the disease and famine, to financial crisis, to politics, to sexual frustration.

I recently finished the book The Monster Hunter in Popular Culture by Heather Duda. In it, she makes a very compelling argument that one of the most remarkable occurrences of the modern monster hunter is that often, he (or she) must in effect be a monster himself. The most obvious version here, at least that our listeners would most likely be familiar with, is Blade, as portrayed by Wesley Snipes (and who appears on the cover of her book). Blade is unambiguously a monster hunter; his job is to kill all vampires. And yet, he is a half-breed vampire himself — one monster hunting the others. Duda has a lot to say about that dichotomy, but the short of it is that in a sense, the monster hunter sacrifices a part of his own humanity in order serve as the savior for the rest of humanity. Though she doesn’t make the connection, I’d argue that there’s perhaps a bit of biblical influence in there even. Certainly there’s an aspect of this that goes back through Joseph Campbell’s classic monomyth. What makes this interesting though is that where the classic hero’s journey may end with the the hero making his great sacrifice, for the monster hunter, at least as Duda defines him, this is something of the beginning of the his journey. Being part monster allows the hunter to be most effective at hunting.

I recently finished the book The Monster Hunter in Popular Culture by Heather Duda. In it, she makes a very compelling argument that one of the most remarkable occurrences of the modern monster hunter is that often, he (or she) must in effect be a monster himself. The most obvious version here, at least that our listeners would most likely be familiar with, is Blade, as portrayed by Wesley Snipes (and who appears on the cover of her book). Blade is unambiguously a monster hunter; his job is to kill all vampires. And yet, he is a half-breed vampire himself — one monster hunting the others. Duda has a lot to say about that dichotomy, but the short of it is that in a sense, the monster hunter sacrifices a part of his own humanity in order serve as the savior for the rest of humanity. Though she doesn’t make the connection, I’d argue that there’s perhaps a bit of biblical influence in there even. Certainly there’s an aspect of this that goes back through Joseph Campbell’s classic monomyth. What makes this interesting though is that where the classic hero’s journey may end with the the hero making his great sacrifice, for the monster hunter, at least as Duda defines him, this is something of the beginning of the his journey. Being part monster allows the hunter to be most effective at hunting.

Even more interesting (at least to me, given the things that I tend to work with) she makes a distinction between the male and female gendered monster hunters. She begins by making a comparison with between the female monster hunter and the final girl of horror movies (defined originally by Carolyn Clover in the excellent book, Men, Women and Chainsaws with the classic example being Laurie Strode from Halloween) and explains that they are not really the same thing. The final girl doesn’t really “hunt” the monster per se. The monster comes after her. Her only purpose is to survive. Duda argues that genre fiction traditionally reserves two roles for the female character, which she refers to as vixen and victim (I have a similar concept in my own dissertation; I call them sexpot and sweetheart — I also add a third classification of sister. The point is literary geeks fucking love alliteration). The vixen is defined by her sexuality and as such, in the patriarchal narrative is traditionally relegated to vixen status. The victim, on the other hand is exactly that. She is pure and innocent and there to rescued by the hero. The final girl is an attempt to bypass that narrative. It allows the victim to gain agency and step into the role of hero in her own right. She can rescue herself. However, to be a final girl, means to implicitly still be a victim.

Even more interesting (at least to me, given the things that I tend to work with) she makes a distinction between the male and female gendered monster hunters. She begins by making a comparison with between the female monster hunter and the final girl of horror movies (defined originally by Carolyn Clover in the excellent book, Men, Women and Chainsaws with the classic example being Laurie Strode from Halloween) and explains that they are not really the same thing. The final girl doesn’t really “hunt” the monster per se. The monster comes after her. Her only purpose is to survive. Duda argues that genre fiction traditionally reserves two roles for the female character, which she refers to as vixen and victim (I have a similar concept in my own dissertation; I call them sexpot and sweetheart — I also add a third classification of sister. The point is literary geeks fucking love alliteration). The vixen is defined by her sexuality and as such, in the patriarchal narrative is traditionally relegated to vixen status. The victim, on the other hand is exactly that. She is pure and innocent and there to rescued by the hero. The final girl is an attempt to bypass that narrative. It allows the victim to gain agency and step into the role of hero in her own right. She can rescue herself. However, to be a final girl, means to implicitly still be a victim.

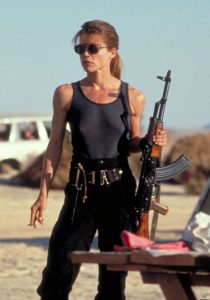

To be a monster hunter on the other hand is to take a more active role. Rather than run away and attempt to escape with her life like the final girl , the monster hunter pursues the monster and places herself in peril. Here we have examples like Ripley in the Aliens series or Sarah Connor in the Terminator series (or at least the second one, the TV series, and the most recent and upcoming movies… she was a final girl in the first). And of course, Buffy. In this sense she gains some of agency of the vixen while maintaining the purity of the victim and final girl. The female monster hunter exhibits a sense of power that had traditionally been reserved for male heroes. However, many of the most popular female monster hunters, dating from Mina Harker in Bram Stoker’s Dracula all the way to the female heroines in Witcher III (just because it’s on my mind from Episode 16), all retain their femininity if not their outright sexuality as well. There is thus an aspect of androgyny about them.

To be a monster hunter on the other hand is to take a more active role. Rather than run away and attempt to escape with her life like the final girl , the monster hunter pursues the monster and places herself in peril. Here we have examples like Ripley in the Aliens series or Sarah Connor in the Terminator series (or at least the second one, the TV series, and the most recent and upcoming movies… she was a final girl in the first). And of course, Buffy. In this sense she gains some of agency of the vixen while maintaining the purity of the victim and final girl. The female monster hunter exhibits a sense of power that had traditionally been reserved for male heroes. However, many of the most popular female monster hunters, dating from Mina Harker in Bram Stoker’s Dracula all the way to the female heroines in Witcher III (just because it’s on my mind from Episode 16), all retain their femininity if not their outright sexuality as well. There is thus an aspect of androgyny about them.

If Duda is right, I would argue that in doing this — in creating a female monster hunter — there is a point where we must read the implicit monstrousness of her monster side in conjunction with the inherent sexuality of her vixen side. And as such, for the female monster hunter, her sexuality becomes linked not only to her masculinity, but also to her monstrousness.

To me this is perhaps best epitomized by a character that isn’t mentioned in Duda’s book at all because she came to popularity after it was published, Sookie Stackhouse of the television series True Blood (based on the Charlaine Harris’s The Southern Vampire Mysteries series of novels). While the character of Sookie begins the series as an innocent and naive virgin, she quickly transforms into both monster hunter and sex addict, unafraid to confront any of the various supernatural creatures that terrorize her city. However, because of her hypersexual appetite and the soap opera nature of the show, she is just as likely to fuck any of them as she is to kill them. In deed, in some cases choosing both, as is evidence by the sexual tryst she has with season 6 big bad, Warlow, whom she captures in sixth episode of the season, binds to tombstone, and seduces — or arguably rapes — despite the fact that he’d spent the previous five episodes attempting to rape, kill and murder her (in that order). Her justification is the monologue she gives while she undresses herself before mounting him:

To me this is perhaps best epitomized by a character that isn’t mentioned in Duda’s book at all because she came to popularity after it was published, Sookie Stackhouse of the television series True Blood (based on the Charlaine Harris’s The Southern Vampire Mysteries series of novels). While the character of Sookie begins the series as an innocent and naive virgin, she quickly transforms into both monster hunter and sex addict, unafraid to confront any of the various supernatural creatures that terrorize her city. However, because of her hypersexual appetite and the soap opera nature of the show, she is just as likely to fuck any of them as she is to kill them. In deed, in some cases choosing both, as is evidence by the sexual tryst she has with season 6 big bad, Warlow, whom she captures in sixth episode of the season, binds to tombstone, and seduces — or arguably rapes — despite the fact that he’d spent the previous five episodes attempting to rape, kill and murder her (in that order). Her justification is the monologue she gives while she undresses herself before mounting him:

“There’s a town consensus about what kind of girl I am. You wanna

take a guess at what it is? They call me a danger whore… I’m thinking maybe they’re right. I have these feelings for you that I don’t wanna have, but I can’t stop myself feeling them. And if this were the first time, I’d probably just ignore it, but, see, there’s a pattern that’s starting to emerge now, so maybe it’s time I just started accepting this about myself… I might be a whore, but I ain’t stupid!”

I’d argue that Sookie is neither stupid nor a whore (she seems to be using the term ironically in response to the slut-shaming she had been receiving prior to this). She is however in many ways a monster. First the scene clearly pushes her well past her original victim portray into the realm of vixen. But also, in accordance with her role as monster hunter her has an inherent monstrousness of her her own, not only because of masculine power she assumes over the course of the series, but also because, like Blade, she is a supernatural half-breed. She is part fairy, and in fact the show explicitly details that it is her supernatural nature that makes her most dangerous to the vampires that she fights. Furthermore it is heavily implied that her fairy origins not only grant her (and the other supernatural creatures) their attractiveness but also their insatiable sexual appetites.

I’d argue that Sookie is neither stupid nor a whore (she seems to be using the term ironically in response to the slut-shaming she had been receiving prior to this). She is however in many ways a monster. First the scene clearly pushes her well past her original victim portray into the realm of vixen. But also, in accordance with her role as monster hunter her has an inherent monstrousness of her her own, not only because of masculine power she assumes over the course of the series, but also because, like Blade, she is a supernatural half-breed. She is part fairy, and in fact the show explicitly details that it is her supernatural nature that makes her most dangerous to the vampires that she fights. Furthermore it is heavily implied that her fairy origins not only grant her (and the other supernatural creatures) their attractiveness but also their insatiable sexual appetites.

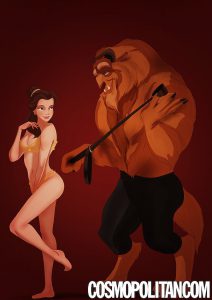

And this is repeated with other monsters… especially with vampires. Dracula was always a sexually charged narrative. Obviously there’s an aspect to this with Buffy and Angel and Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles. And to get more current, it’s the central premise to the Twilight series. But even beyond vampires, where the allusion is obviously explicit, it seems to be an undertone of other monster narratives. After all, exotic sexuality (with racially charged undertones) has always been kind of a backdrop to things like King Kong. The sexuality inherent in the werewolf myth is explored in Angela Carter’s short stories “The Company of Wolves” and “The Bloody Chamber”. Even the basic narrative of Beauty and the Beast revolves around sex. You know, just Disneyfied in most people’s minds… but really, the story is totally about fucking a monster (something that the Internet has totally picked up on… because it’s the internet). And the parts that aren’t about fucking a monster — even in the Disney version — are all about Belle’s attempts to challenge traditional gender roles.

And this is repeated with other monsters… especially with vampires. Dracula was always a sexually charged narrative. Obviously there’s an aspect to this with Buffy and Angel and Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles. And to get more current, it’s the central premise to the Twilight series. But even beyond vampires, where the allusion is obviously explicit, it seems to be an undertone of other monster narratives. After all, exotic sexuality (with racially charged undertones) has always been kind of a backdrop to things like King Kong. The sexuality inherent in the werewolf myth is explored in Angela Carter’s short stories “The Company of Wolves” and “The Bloody Chamber”. Even the basic narrative of Beauty and the Beast revolves around sex. You know, just Disneyfied in most people’s minds… but really, the story is totally about fucking a monster (something that the Internet has totally picked up on… because it’s the internet). And the parts that aren’t about fucking a monster — even in the Disney version — are all about Belle’s attempts to challenge traditional gender roles.

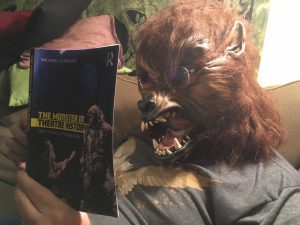

So if monstrosity is all about sexy, mixed with supernatural power, and if a monster can represent anything, and if a monster under is part monster, then what is a monster anyway? For that I would look to a different text, The Monster in Theatre History by Michael Chemers. It details ummm…. well… the history of monsters… umm… as they’ve… you know… been portrayed in the theater. Unfortunately, as you might surmise by me stammering like a 9th grader who hasn’t finished reading the book before trying to give his oral report… I haven’t actually finished reading the book. But Wayne has. And in fact, he knows Chemers personally, so i’m going to turn things over to him for a bit.

From Wayne: I hesitate to try to write a summary of my friend Dr. Michael Chemers book, The Monster in Theater History. He’s the expert and would no doubt gently correct all of my misconceptions. The back cover copy of the book reads:

The Monster in Theatre History explores the cultural genealogies of monsters as they appear in the recorded history of Western theatre. From the Ancient Greeks to the most cutting-edge new media, Michael Chemers focuses on a series of ‘key’ monsters, including Frankenstein’s creature, werewolves, ghosts, and vampires, to reconsider what monsters in performance might mean to those who witness them.

The book traces the appearance of the monster very specifically in the context of the theater, but traces the lineage of the folktales that inspired these stories, as well as looks at how the plays are tied to the various other media that they have inspired.

I personally find it telling that the title of the introduction is “The Dramaturgy of Empathy.” Why do we empathize with the Monster? What can we learn from its existence. Mike comes from a background that includes not only theater studies but also disability studies. There is the element of the Monsterized Other in the way society has traditionally dealt with the disabled. Our Monster stories are a reflection of the way we think about any kind of social deviance from the perceived norm. The traditional horror story typically serves as a sort of morality play. People and monsters do terrible things, but in the end they pay the price for their transgressions and the “normal” social order is restored. That is a trope that has changed over the years but still lies at the base of the genre.

So what can we learn from empathy for the Monster? The Jungian archetype of the Shadow represents all of the elements of our personality that we reject. It is our dark, monstrous side. To be psychologically healthy we must not only confront our shadow, but also integrate into our persona. This sounds a lot like what Heather Duda is saying about monster hunters needing to be monsters as well.

So what can we learn from empathy for the Monster? The Jungian archetype of the Shadow represents all of the elements of our personality that we reject. It is our dark, monstrous side. To be psychologically healthy we must not only confront our shadow, but also integrate into our persona. This sounds a lot like what Heather Duda is saying about monster hunters needing to be monsters as well.

At the Golden Globes Guillermo del Toro said this in his acceptance speech:

“Since childhood I’ve been faithful to monsters — I have been saved and absolved by them. Because monsters, I believe, are patron saints of our blissful imperfection.”

Perhaps the Abyss gazing back isn’t always a bad thing.

From Mav: So why is this exciting? Well, partly just because it is. But also, because both Heather Duda and Michael Chemers are going to be our guests on this episode as we try to hash through exactly what is the relationship between monster and monster hunter and why we relate to them both so much in modern pop culture. What are your thoughts? Do you buy into their arguments? Do you not? Do you have theories or readings of your own? What do you think we should explore as we talk to Heather and Michael? We’re excited about this one, so we really want your feedback.

First of all, I can’t wait for this episode! Secondly, I think the Frankenstein mythology is interesting because in the novel it starts with the doctor as the monster hunted by the creature (Victor doesn’t hunt him till after the creature kills his wife). However most people are more familiar with Karloff films that reverse that dynamic.

Another interesting book/movie dichotomy is in Moore’s From Hell where what would be the physically noticeable monster is Joseph Merrick (Elephant Man) who is written as gentle and the outwardly normal Ripper who is the greater threat. (The prostitutes are also treated as monstrous by society).What does the monster hunter (Inspector Abberline) do in this situation? (Spoiler alert he is pretty ineffectual in the novel)

Guillermo del Toro’s whole oeuvre is relevant here — pan’s labyrinth contrasts fantastic monsters with human ones (in some ways it and Neil Gaiman’s Coraline are very similar and might be worth comparing); Hellboy of course was a movie he wanted to make for a long time because it was about monsters who are not monsters; we understand Hellboy and Liz and Abe as people first and monsters second. And then, of course, monsterfucking.

I have a lot more thoughts about this but I’m on my phone so you’ll have to make do w GDT.

I love that you mentioned Conan, because not only has that trope/plot continued but it has obviously inspired similar franchises such as the Manga/Anime “Berserk” where the main hero is eventually thrust into a monstrous apocalyptic wasteland and branded with a brand that attracts demons to him (the brand being the result of a demonic ritual in which he was branded as a sacrifice prior to his escape.) So he fulfills the role of both being the hunter and the hunted (similar to Buffy) just carving things up with his oversized anime sword.

There’s also the Manga/Anime aptly named “Monster” which stars a doctor who saves the life of a child who grows up to be a mass murdering would be Hitler/Joker/etc. type. But, along the way this altruistic Doctor begins to lose more and more of his humanity on his vigilante quest to correct his mistake (saving a life) for the greater good.

So, yeah, I think there is 100% something there about monster hunters becoming monsters themselves… you could even apply this same logic to a character like Batman (or other vigilantes like Punisher) depending on who is writing him and how they’re writing him.

PS. Also, video game nerd fact check: Are you mixing Resident Evil with House of the Dead? :p There is a singular RE arcade game but it’s pretty obscure.

Had a recent chat with Dr. Chemers about the difference between monsters and other run-of-the-mill antagonists. I’d love to hear some more along that line.