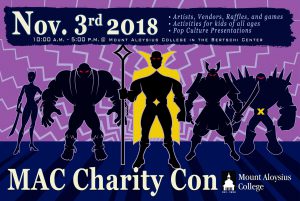

From Mav: Even though we haven’t recorded this next week’s show just yet (we’re doing it tonight, so you still have a chance to throw in some comment on Monsters, so check that Call for Comments) we’re already planning another one. This Saturday, I will be appearing at MAC Charity Con in Mt. Aloysius, PA. I’ll be giving a talk on how sexiness works with supervillainesses (and super heroines to a lesser extent). If you’re in the area (it’s about an hour or so outside of Pittsburgh) and you’ve always wanted to see me talk about my comics research about where sex, gender and superheroes all meet up together, here’s your chance. While there, you’d also get to see some presentations by some great people who aren’t me, and I’ll be appearing on a live episode of the Sectarian Review Podcast, hosted by friend of the show Danny Anderson, AND we’ll be recording a live episode of this show. Even if you’re not going to be there, that’s where you come in.

From Mav: Even though we haven’t recorded this next week’s show just yet (we’re doing it tonight, so you still have a chance to throw in some comment on Monsters, so check that Call for Comments) we’re already planning another one. This Saturday, I will be appearing at MAC Charity Con in Mt. Aloysius, PA. I’ll be giving a talk on how sexiness works with supervillainesses (and super heroines to a lesser extent). If you’re in the area (it’s about an hour or so outside of Pittsburgh) and you’ve always wanted to see me talk about my comics research about where sex, gender and superheroes all meet up together, here’s your chance. While there, you’d also get to see some presentations by some great people who aren’t me, and I’ll be appearing on a live episode of the Sectarian Review Podcast, hosted by friend of the show Danny Anderson, AND we’ll be recording a live episode of this show. Even if you’re not going to be there, that’s where you come in.

The topic we’ll be discussing is anti-heroes. Once upon a time, the difference between heroes and villains was simple; the guy in the white hat was the good guy and the guy with the black hat was the bad guy. As a reader it was immediately clear whom to root for. Over time, this became more complicated. A succession of vigilante characters like the Punisher, Rorschach, and Deadpool blurred the lines between good guys and bad guys. Popular villains like Venom, and Deathstroke were given their own comics where they were nominally the heroes. Heroes that display many of the traits commonly associated with villains.

The topic we’ll be discussing is anti-heroes. Once upon a time, the difference between heroes and villains was simple; the guy in the white hat was the good guy and the guy with the black hat was the bad guy. As a reader it was immediately clear whom to root for. Over time, this became more complicated. A succession of vigilante characters like the Punisher, Rorschach, and Deadpool blurred the lines between good guys and bad guys. Popular villains like Venom, and Deathstroke were given their own comics where they were nominally the heroes. Heroes that display many of the traits commonly associated with villains.

But, is this truly a new phenomenon? Batman began his career as a murderous vigilante. Similarly, the Phantom and the Shadow displayed these antihero tendencies as far back as the 1930s. Even Superman displayed many antisocial tendencies, rather than the perennial Boy Scout we know today, when he was first introduced. Even in the Netflix Daredevil series second season, which features interplay between the outlaw hero Daredevil and the outlaw antihero Punisher, the question is directly asked, what is it that separates the two? And there’s no clear answer given.

But, is this truly a new phenomenon? Batman began his career as a murderous vigilante. Similarly, the Phantom and the Shadow displayed these antihero tendencies as far back as the 1930s. Even Superman displayed many antisocial tendencies, rather than the perennial Boy Scout we know today, when he was first introduced. Even in the Netflix Daredevil series second season, which features interplay between the outlaw hero Daredevil and the outlaw antihero Punisher, the question is directly asked, what is it that separates the two? And there’s no clear answer given.

And this extends to other media beyond comics as well. Any number of video games about “heroes” ultimately feature a plot line wherein your job as a player is to kill as many villains as possible. While there may be storyline reasons that differentiate the motivations, the actual mechanics of the actions you partake in are often independent of this. So if that’s the case do the motivations actually matter? What makes the classic cowboy a hero? He shoots just as many people as the bad guys. Sometimes even more. Even in old westerns, many of the characters played by Clint Eastwood are outlaws. Even the most generic stereotype of the wild west gunslinger is rough around the edges — antisocial — even while fighting for the public good. This extends to the hard-boiled detective of film noir and every action hero ever played by Bruce Willis. And other people too… but definitely every character Bruce Willis plays.

And this extends to other media beyond comics as well. Any number of video games about “heroes” ultimately feature a plot line wherein your job as a player is to kill as many villains as possible. While there may be storyline reasons that differentiate the motivations, the actual mechanics of the actions you partake in are often independent of this. So if that’s the case do the motivations actually matter? What makes the classic cowboy a hero? He shoots just as many people as the bad guys. Sometimes even more. Even in old westerns, many of the characters played by Clint Eastwood are outlaws. Even the most generic stereotype of the wild west gunslinger is rough around the edges — antisocial — even while fighting for the public good. This extends to the hard-boiled detective of film noir and every action hero ever played by Bruce Willis. And other people too… but definitely every character Bruce Willis plays.

So we want to look at that. Specifically, “what makes them interesting?” But also what defines them? What’s the difference between a hero, and anti-hero and an outright villain anyway? Wayne often says that one of his problems with the way that the Punisher exists in the Marvel Universe, is that he doesn’t see how Captain America sleeps at night in a world Frank Castle roams free. And he’s right, there is a bit of a disconnect there. One of my all time favorite Captain America comic storylines was in the mid to late 1980s when Cap tracked down the Scourge of the Underworld, a vigilante who was murdering super-criminals while shouting “Justice is served”. How do we reconcile the Punisher, who began his own comic series as a hero concurrently with Captain America devoting himself to tracking a villain with the exact same premise. How can those two books exist next to each other on the same shelf in a comic book store? And yet they did.

So we want to look at that. Specifically, “what makes them interesting?” But also what defines them? What’s the difference between a hero, and anti-hero and an outright villain anyway? Wayne often says that one of his problems with the way that the Punisher exists in the Marvel Universe, is that he doesn’t see how Captain America sleeps at night in a world Frank Castle roams free. And he’s right, there is a bit of a disconnect there. One of my all time favorite Captain America comic storylines was in the mid to late 1980s when Cap tracked down the Scourge of the Underworld, a vigilante who was murdering super-criminals while shouting “Justice is served”. How do we reconcile the Punisher, who began his own comic series as a hero concurrently with Captain America devoting himself to tracking a villain with the exact same premise. How can those two books exist next to each other on the same shelf in a comic book store? And yet they did.

So what are your thoughts? What makes a hero vs. an antihero? What else should we discuss on this topic?

Related

Call For Comments: MAC LIVE show and the antihero?

October 31, 2018

So what are your thoughts? What makes a hero vs. an antihero? What else should we discuss on this topic?

Share this:

Related