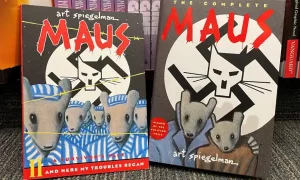

From Mav: So, I guess we need to talk about “the Maus situation.” If you live in my world then it’s pretty impossible to escape the news from last week that Art Spiegelman’s Maus was “banned.” Between the fact that it’s a comic, that it was a politically motivated book banning, that there are issues of racism, that there’s questions of marxism and hegemony and capitalism and identity politics… in some ways, the whole Maus situation is pretty much just the very confluence of every aspect of literary and cultural studies that pervades my life. In case you missed it (and, honestly, unlikely anyone who listens to our show could have possibly missed it, but for posterity), last week it was reported that a Tennessee school board “banned” Maus because of its explicit content (foul language and nudity) and the internet went into an uproar talking about banned books and antisemitism. In the interest of full disclosure TECHNICALLY the book wasn’t banned so much as “removed from the curriculum.” This is largely a distinction without a difference in this case, but I am mentioning it because if I don’t someone probably will complain and try to “well actually…” me (and because the tiny little nuance is going to matter a bit before I’m done).

Anyway, as more details have come out, the whole thing is even stupider because it turns out that the school board members who… ok if I can’t call it “banning” the book, can I call it “cancelling”… the school board members who cancelled Maus totally didn’t even read it and don’t really seem to really know why they’re cancelling it other than in a misguided attempt to show that they’re the moral authorities… without doing any of the actual hard work it takes to become an authority on something… or at least doing the hard work of… you know… reading a comic book. And yes, I know that Maus is a very deep and complex comic. But that’s the point… I know that cuz I’ve read it! They didn’t and so they don’t! They’re a bunch of zealots who can’t be bothered to read a fucking comic book… but think they have the intelligence to make moral and educational decisions. And predictably the whole thing backfired, because of course Maus is now at the top of the best seller list for the first time in ages. At the very least, that’s a good thing. It’s also a good thing because it has the nation discussing the holocaust and how antisemitism fits in with other forms of racism (as Whoopi Goldberg is suddenly finding out on The View).

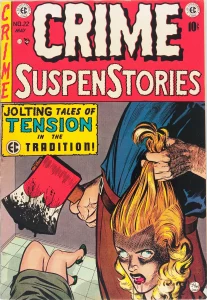

It’s also good because it has people talking about the very concept of banned books. This isn’t actually new. I think this incident is getting even more traction than normal specifically because Maus is a comic, which sort of makes it part of our current pop culture zeitgeist in a way that other books aren’t always. There’s a long history of comics being banned — hell, the entire industry is STILL in many ways structured around the Comics Code Authority (CCA) which was designed specifically to censor content. Basically, the CCA banned books for 56 years starting in 1954. That was its sole reason for existing. Comics are still affected by it even though it’s been defunct for more than a decade! But Maus being banned it noticeable and relevant because geeks (and the cultural zeitgeist) tend to focus on things right in front of their face, often missing a wider context.

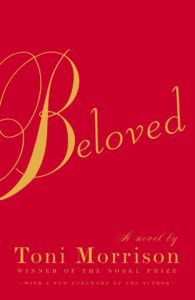

And since popular culture is geek culture right now, seeing the banning of a the only Pulitzer Prize winning comic certainly grabs attention. But the hosts of VoxPopcast have talked about doing a show on book banning before. Most recently I was thinking about it a few months ago when banning Toni Morrison’s Beloved became an issue in the lead up to the Virginia governor’s election. We didn’t get around to it back then, but you know… it was obvious it would happen again. And so here we are. By the way, Beloved also won the Pulitzer. So did The Color Purple, which is also frequently banned. Same with To Kill a Mockingbird. In fact, the truth is winning the Pulitzer for writing about racism is a pretty good way to get people to try to ban you.

And it’s obvious where we’re going to fall on the issue for this show; we’re a bunch of literature scholars, who are all pretty vocally liberal about this sort of thing, and you can kind of just guess. But I want to think a little bit about WHY people keep trying to ban books or cancel them or whatever it is you want to call it. Yes, it’s simple to say “they’re doing it for racism.” And sure… they are. But I don’t think it’s that simple. About the best breakdown I’ve seen of this in the last week was a viral Twitter thread written by my and Katya’s former professor, and previous guest of the show, Dr. Kathy Newman:

If you’ve not seen the thread before, you should definitely read it. It’s very good. One of Kathy’s key points I want to focus on is that no one ever really bans books specifically “to be racist” (or sexist or antisemitic or anything else -ist). That’s just not how people think. It’s almost always under the auspices of protecting children from something harmful… often ideas that don’t fit the ideological purity of whoever is doing the banning. Basically they’re always doing it for “the good reasons.” They’re wrong, but that’s their intent. The thing is, if you don’t subscribe to those ideologies, it always seems obviously bathsit crazy. But, just for a moment I want to think about what it’s like if you DO subscribe to those ideologies. Because I’ve run into a LOT of otherwise liberal parents over the years who are completely against banning books … except obviously they don’t mean stuff like kiddie porn. But, that’s not the same thing, right? Ahhh… see, nuance! Should I be able to teach 8th grader’s Stephen King’s It complete with the orgy scene in the sewers? What about something like the movie Cuties with hypersexualized 11-year olds? Because remember… we did a whole show on it!

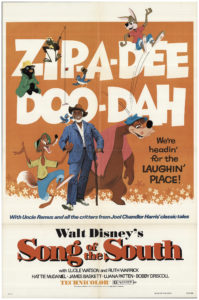

Or moving beyond that, what about the whole show we did about cancelling Pepe LePew and Dr. Seuss? Or what about racist films like Gone With The Wind and Song of the South? Because we did a show about that too! And in each of those cases, I personally argued AGAINST censoring the media. Partially because I actually enjoy Gone With the Wind, Song of the South, Cuties and old Pepe LePew cartoons even with the problems of which I am fully aware. And just last week we talked about the older Nancy Drew books that had lots of casual racism and then were rewritten to literally whitewash it out. But moreover, I think we have a lot to learn by consuming problematic texts and then discussing, analyzing, and learning from them. And yes, that wasn’t the same… because in some cases the media owners have simply decided to remove their IP from circulation themselves and in others the films have been “modified to add context” and that feels “different”. But like I said … NUANCE! But the thing is, people in the midst of being upset about something that offends their personal sensibilities for reasons that seem honest to them… aren’t great at seeing nuance in moment… if ever!

But nuance is what we do here! So we’ve invited Kathy back to talk about the history of banned books, the reasons people do it, the reasons people fight it, what and culture behind it, what we can learn by reading and studying banned books, and the nuances of different situations. So give us your thoughts and questions on the concept of banning and censorship so we can talk about them on our next episode.

I’d be interested in hearing your take on the similarities between the mindset that says, “The person who wrote this book is a deviant, but is hiding it from the world in an attempt to pervert our children,” and the mindset that says, “The person who’s removing this book from curriculum is a racist, but is hiding it from the world in an attempt to pervert out children.”

The first group, which is the group that has the power to affect change, is obviously more of an issue on a practical level, but I think it would be useful to think through, especially for those of us who want more people to read good books.

Might be a comment too late to add, but I definitely see the banning of Maus as a haunting of Wertham’s comic panic and the creation of the Comics code. A simple answer, maybe, but for me it draws out the anxieties of what children are taught and allowed to consume, a cementing of boundaries on which media is “good” media to the state apparatus, the institution of the community, if not (at this moment) also political figures trying to secure and keep their positions and financial support. If this is a haunting of Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, then it could open space to think about how comics and media continued to be affected by different varieties of the low-brow/high-brow consumption of art and literature.