From Mav: So, like a lot of other people I used the Lensa app to make myself a collection of random avatars last weekend. Why? Because all of my friends were doing it and if they were all going to jump off a cliff I would too. And yeah, that sounds silly, but honestly, that’s kinda what popular culture is. Going with the zeitgeist. Something became cool and memeable and I had to get in on it, because I am a cool kid, dude! And I’m kind of glad I did because I learned some really interesting things about myself based on decisions the AI made about me: 1) I can probably rock some dreds, or at least some twists in my hair, or I could even just “go full dragonball” and look pretty cool 2) I should also get more tattoos because the AI thinks I would look cool with a full arm sleeve. 3) I need to work out and get some superhero abs going, because I haven’t seen the stomach the AI thinks I have in like 20 years.

That said, even when I was first making them, I knew that there was going to be a little bit of controversy around this and I knew what it would be. And of course, I didn’t even get through the weekend before I started seeing people posting … let’s call it “activism by meme”. Basically people are posting arguments that you shouldn’t be making these avatars because they amount to theft from the artists who were used to train the AI. In my favorite, there’s some nebulous complaints about this not really being fair use and a comparison to stealing a car… which is a favorite complaint about people talking about digital rights and complete nonsense and then a call for people to educate themselves before using these tools. The problem is, education doesn’t come from just reading other people’s random social medial complaints and then sort of picking the ones you sort of kinda agree with.

I ran into this argument a couple months ago when everyone was using Midjourney after John Oliver posted about it, and my cohost from my other show, Andrew Deman, and I made some fan art of the Marvel comics character Magik using these. Someone tried to yell at us on Twitter because “if we really understood what was going on we’d never support this.” I actually tried to engage with one of them explaining that I did know how it worked and starting talking about the complexities remix culture and derivative works and then the guy blocked me… which I found fascinating because the whole conversation started because he wanted to talk to me about something I did. I figured I might do a show about it then, but I didn’t get around to it.

Then, a fascinating thing happened BESIDES just the Lensa thing. Something that probably didn’t get as much press unless you are in the tiny subset of the internet that is comic book artists. Celsys, the makers of a graphics program called Clip Studio Paint (which I love and which I used to use to draw Cosmic Hellcats back when we were working on that) announced that the next version of the software would have some AI image generation tools based on the Stable Diffusion platform (the same thing that Lensa uses). But since the tool primarily serves tech-weenie comic artists, there was a large vocal backlash and Celsys reversed course and announced that they were removing that feature. In other words, a software company opted to stop development on a tool that their competitors are absolutely going to adopt — sacrificing their competitive advantage — because their user base has an uninformed idea of what that tool actually is. That’s when I realized there was definitely something here and we had to do a show about it. The fervor around Lensa this week just cemented it.

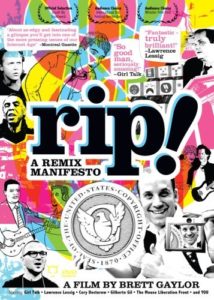

The thing is, I get why people are worried about this, and honestly, some of the worries are valid, but the situation is a lot more complex than just saying “oh this is theft from real artists.” This is a complex web of ethics and culture and laws and algorithms and feelings and despite what people are acting like, it’s not really unique to AI artwork… or even AI in general. Part of this has to do with concepts we’ve talked about before, like on our Deep Fakes episode. But it goes beyond that too. This extends into conversations that have been going on for decades in the music industry because of cheaper digital recording and the availability of sampling (I highly recommend the free documentary RIP!: A Remix Manifesto if you’ve never seen it)… which ultimately resulted in the birth of hip hop and continuous controversy related to it. It extends beyond that to the discover of technologies like the photograph and… the printing press… and… well… the book. Actually that last comment was one of the things that made the rando on Twitter block me. I guess he assumed I was trolling him. I wasn’t! I think about this a lot. Like really a lot! It’s foundational to one of the classes I’m teaching this semester in fact!

The whole thing is wrapped up in a very complex question of “what is an original work of art anyway?” This is not as simple a question as it seems like. I can draw! I went to art school! Ok… but can I draw? I can sort of draw, but in all honesty, I’m not really doing anything TRULY innovative. My art is really a weird amalgamation of my attempts to replicate a meshing of Jack Kirby, John Buscema, John Romita Sr., John Romita Jr., Frank Miller, Art Adams, Jim Lee, Frank Cho, Matt Baker, Amanda Conner, Kenichi Sonoda, Izumi Matsumoto, Patrick Nagel, Jennifer Janesko, Dennis Mukai, Burne Hogarth, Richard Tibbits, Leonardo DaVinci, and probably bits and pieces of two dozen other people. Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and all the other AIs are literally doing the exact same thing (as is DeepFake). I’m just not as good at it as the computer is. And my inability to be perfect actually results in stylistic quirks that feel uniquely me. BUT, I’d argue the digital artwork has this same feature.

And even beyond just the technical and artistic stuff, there are much deeper issues of culture and hegemony and believe it or not, Marxism! Well, Marxism and Neoliberalism. Basically, this whole issue is sort of born a weird mixing of fairly progressive ideas about the importance of culture and art with a merger of trying to trap it within a very specific view of capitalist property rights that don’t really scale the way people sort of want them to.

And of course, obviously the whole thing is just more seeding of the database with your digital images so that it can grow. Basically we’re helping them “steal” from us.

So yeah… we want to talk about all of that. BUT FIRST, we want to know your thoughts before we record. Where do you stand on the general concept of AI art? Where do you stand on the argument that it’s theft? Do you think this is the end of artwork? Is it the beginning of the robot uprising? What questions do you have about how it works or the cultural issues associated with it? What things do you think we should be embracing or fearing. Let us know in the comments so we can talk about it on the show.

I’m more curious about this other aspect of the conversation about Lensa. But maybe that’s a different episode

Theft is a part of art. It always has been – the question is where you draw the ethical boundaries, and what you do when you cross them.

I think using artists’ work as training data for a product that makes money for people who aren’t the artists might be theft (or just ethically wrong, since I think existing laws probably aren’t going to decide this is illegal). I think a lot of the anger might go away if people were offered compensation in exchange for choosing to let their art be in the training database. The art itself is not stolen though, IMO. I keep seeing people compare it to collage or “copying and pasting art” and that’s just not how AI works.

AI art, as it stands, is very probably theft. The AI uses existing art by actual humans to “learn” and apes that art to make its new finished product. Using AI to make something is akin to being an accessory to the crime. Some of it is very cool… but only because some human somewhere already created something cool.

Here thanks to Jessi Bencloski. I’m working on an AI project right now that uses multiple types of models (including Stable Diffusion). You are right in that there is a lot going on with AI right now. And since this is about art, let’s start there. What Stable Diffusion (and by extension all of the popular art AIs do) is use the art in their training data as “inspiration” for the art they create. Most of the time, that art is gathered by simply scraping art off the web. Whether or not that is ethical, it is legal. And since the art created by SD (and by extension other art AIs) is different enough that it doesn’t interfere with copyright, it’s legal to post. The ethics of generative AI is incredibly complex. There’s a ton of stuff involved, and it’s been known for years within the AI industry that these are going to be tough hurdles to overcome. What the public DOESN’T realize is how incredibly fast these things are moving. The learning algorithms used in AI have become almost unbelievably efficient, and industry professionals have mostly worked out the bugs in how to build training datasets. We will still have issues as new people move into the field and mess around, but we can train our own version of SD with unique creations on a PC that costs less than $4k, and most of that cost went to being able to crank out new images in less than 2 seconds. If you don’t mind waiting, you can do it on a regular PC (or Mac) with a decent graphics card, and with as few as 5 images. Large Language Models (things like GPT-3, the text version of Dali-2) is considerably more complicated. Text is harder than art. Coloring pixels is a considerably easier problem than figuring out what letter or word comes next. But there are still free versions of these models as well. BLOOM, the open-source answer to GPT-3, is something we are using right now. It’s considerably more resource heavy than Stable Diffusion, but that $3k-ish machine we built for that purpose can still do it. But back to art, since that’s the purpose of this talk. I was talking to Jessi when all this controversy started. AI isn’t going away. On the contrary, it’s only going to get cheaper and more available, which is going to make things like LENSA more common. What needs to happen is that artists need to join in, rather than boycott. It’s really not that hard to get on the bandwagon. We built a machine, but that’s only so that we can do this at an industrial scale. Any artist with a decent Mac should be able to run SD, and maybe even train it. The guy I’m working with is a designer, an art professional. He bought into AI wholeheartedly. He uses it whenever possible to aid his process, and artists should too. This represents a chance for artists to automate their process, to make their lives easier. Anytime an industry has become automated, those who bought in prospered and those who didn’t generally got left behind. With open-source software available this time, artists have the opportunity TO buy in. Fighting it is just going to cause them to get left behind.

Part of me really wants to start this episode with the Dusty Rhodes’ Hard Times speech… but Anthony Ruttgaizer would be the only person who got the reference.

I’d like to introduce you to my friend Suzanne Szucs, who has a lot of interesting things to say about this. She’s an artist, art professor, and all around shining star. Suz, Mav is a brilliant comics and pop culture scholar.

So I come to this stuff from the perspective of an IP attorney, which means I’m focusing on somewhat different questions. I’ve been looking at whether these works are copyrightable and, if so, by whom (which I put here: unmakeme.com/2022/07/15/the…). Of course, the general discourse has been more in the topics you raise here, focusing on whether original artwork was stolen to train the AI models. Fair use gets raised a lot, but I don’t think fair use is really the right way to frame the issue. I think the more compelling question is whether the AI models are even copying the originals in the first place. Obviously they need to use a copy of the original artwork when they initially train the AI model, so there’s a copy at that stage. But there’s a lot of art out there that is free to view, and I’m just not convinced that an AI model “viewing” and learning from the original is all that different from a human being doing it. You raise this point in the analogy to humans learning how to draw, and I think that’s the right way to approach it. When you draw something that relies on the stylistic influence of the artists you’ve seen before, you aren’t creating a copy at all, but are instead creating a new piece of art. You haven’t stolen anything but inspiration. Part of the furor comes, I think, from the Luddite-esque fear that AI models will make human artists obsolete. But another part stems from a mismatch between what the law protects and people’s intuitive sense of fairness. I’ve gotten into this fight over and over in the world of stationery, where people get in a tizzy over knockoffs of pen designs that have been in the public domain for decades. Some people have a very middle-school ethic that says, “Copying is always bad!” They’d be just as mad at a human copying the style of an established artist as they are at a machine doing it. Consider if you started making and selling art in a convincing imitation of Ditko’s style–some people would call you a hack and some people would love it. You wouldn’t be copying any given piece of art, but some people would still give you crap because they regard “style” as being something it is wrong to copy (or at least to profit from), even though copyright law doesn’t cover it at all. The rhetoric over stealing art from human artists seems to come from that place–some people’s basic ethical judgment that it is always wrong to use another artist’s works for your own profit. I think it’s fair to say that the companies training AI models on pre-existing artwork are doing that. But the current state of copyright law is a compromise between that absolutist ethical position and the practical realities of operating in a world with uncounted millions of artists, all of whom are trying to do their own thing in the pre-existing context of their own cultures. The things that a company does to train an AI model, and the output of that AI model, don’t seem like they fall within the scope of existing copyright law. So long story short, I just don’t see AI art as theft, and I don’t think the law is going to change to turn it into theft. The same questions we’re facing now for this new technology are questions we have already answered when it comes to humans, and we have already reached a stable compromise on it. The fact that we have machines doing it now doesn’t seem like it moves the ethical needle much.