From Wayne: We all have our favorite genres in our choice of entertainment. I like superheroes and science fiction and some kinds of Horror. I’ve recently discovered an affection for Thrillers. I used to think I didn’t like Crime stories, but that has changed. I don’t read a lot of Romance books, generally speaking. When I go into a bookstore I browse these sections and tend to skip over the sections for Sports or Business. In record stores (remember those?), I really never check out the sections for Jazz or Classical or Opera. These choices aren’t really meant as indictments, just reflections of my tastes and interests.

From Wayne: We all have our favorite genres in our choice of entertainment. I like superheroes and science fiction and some kinds of Horror. I’ve recently discovered an affection for Thrillers. I used to think I didn’t like Crime stories, but that has changed. I don’t read a lot of Romance books, generally speaking. When I go into a bookstore I browse these sections and tend to skip over the sections for Sports or Business. In record stores (remember those?), I really never check out the sections for Jazz or Classical or Opera. These choices aren’t really meant as indictments, just reflections of my tastes and interests.

But what is genre, really? Is it primarily a marketing term so that people can narrow down their searches? I’ve been told by publishers and agents that they really need to be able to pinpoint a specific genre so that they can effectively market a product. What are the limits of genre? We know a superhero story when we see one, don’t we? Maybe not. What are the limits of the tropes we associate with each of these genres and how do these limitations also limit the content of what we enjoy?

But what is genre, really? Is it primarily a marketing term so that people can narrow down their searches? I’ve been told by publishers and agents that they really need to be able to pinpoint a specific genre so that they can effectively market a product. What are the limits of genre? We know a superhero story when we see one, don’t we? Maybe not. What are the limits of the tropes we associate with each of these genres and how do these limitations also limit the content of what we enjoy?

Many of the things we most enjoy in the “Geek community” transcend the specific definitions of genre. It’s usually a good thing for content, not so good for marketing. Firefly was a Western, except when it was being a Science Fiction show. Many years later there is still an avid fanbase for a show that was cancelled because it confused a lot of the audience and the network execs.

Many of the things we most enjoy in the “Geek community” transcend the specific definitions of genre. It’s usually a good thing for content, not so good for marketing. Firefly was a Western, except when it was being a Science Fiction show. Many years later there is still an avid fanbase for a show that was cancelled because it confused a lot of the audience and the network execs.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe is a great example of this. It’s a superhero universe, yes, but it’s a lot of other things as well. Captain America: The Winter Soldier is a political thriller. Ant-Man is a heist movie. Thor is an epic fantasy. Guardians of the Galaxy is a scifi comedy. But they all comfortably exist in the same continuity.

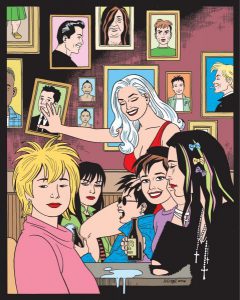

So we’re going to talk about this. One of my favorite long running comics, Love & Rockets, is a mashup of many genres. Riverdale (yeah… we’re gonna talk about Riverdale again), is a mashup of many genres. We’re going to try and figure out just what genre is and if it’s an outmoded concept in a postmodern world. I’m going to leave you with this quote from Alan Moore.

So we’re going to talk about this. One of my favorite long running comics, Love & Rockets, is a mashup of many genres. Riverdale (yeah… we’re gonna talk about Riverdale again), is a mashup of many genres. We’re going to try and figure out just what genre is and if it’s an outmoded concept in a postmodern world. I’m going to leave you with this quote from Alan Moore.

“My experience of life is that it is not divided up into genres; it’s a horrifying, romantic, tragic, comical, science-fiction cowboy detective novel. You know, with a bit of pornography if you’re lucky.”

―

From Mav: To me the idea of genre is fascinating. For one thing, there was a time, not too long ago, where genre was “a bad word.” When I was getting my Creative Writing degree, one of the rules was “no genre” because my teachers wanted us to learn how to write good characters first, without using genre conventions as a crutch. We still see this today. The Oscar for Best Picture usually goes to a film that is dramatic and serious and artsy. Films about human interest and struggle — “High Art!” While we traditionally think of “genre fiction” as garbage fed to the unwashed masses. Of course, it’s now 2018 and superhero movies make billions of dollars. And other films that lean heavily on genre makes hundreds of millions. So this is changing. I’m not sure this was ever true anyway. I think even your high art stories were often in some genre or another. It just might not have been as obvious. But, like Wayne said, that begs the question, just what is genre anyway?

From Mav: To me the idea of genre is fascinating. For one thing, there was a time, not too long ago, where genre was “a bad word.” When I was getting my Creative Writing degree, one of the rules was “no genre” because my teachers wanted us to learn how to write good characters first, without using genre conventions as a crutch. We still see this today. The Oscar for Best Picture usually goes to a film that is dramatic and serious and artsy. Films about human interest and struggle — “High Art!” While we traditionally think of “genre fiction” as garbage fed to the unwashed masses. Of course, it’s now 2018 and superhero movies make billions of dollars. And other films that lean heavily on genre makes hundreds of millions. So this is changing. I’m not sure this was ever true anyway. I think even your high art stories were often in some genre or another. It just might not have been as obvious. But, like Wayne said, that begs the question, just what is genre anyway?

At its base, it just implies a kind of bucket of the kinds of story conventions and tropes that the creator and consumer can take for granted that each other are aware of. I don’t have to explain why it’s ok for people to just be able to fly in my superhero story, I don’t question the fact that people can just shoot each other at high noon with little consequence in my western, and I understand that in my romantic comedies people can run through the airport screaming each others names and then embrace and start making out without TSA tackling them to the ground and arresting them. Genre sets the rules for the world the characters inhabit.

Of course, this means that interesting things happen when the author can break the accepted rules of the genre and disrupt the reader’s expectations. This is what happens with the film (and comic) Kick-Ass, for instance where characters behave as though their world follows superhero genre conventions, but the comedy and plot derive from the fact that it doesn’t. We have similar situations arise when we mix genres together as Wayne was saying above. Firefly can’t just happen as an Earth western, and it wouldn’t be the same if it were just a standard issue Star Trek space fantasy either. It requires the elements of the disparate genres to mix.

Of course, this means that interesting things happen when the author can break the accepted rules of the genre and disrupt the reader’s expectations. This is what happens with the film (and comic) Kick-Ass, for instance where characters behave as though their world follows superhero genre conventions, but the comedy and plot derive from the fact that it doesn’t. We have similar situations arise when we mix genres together as Wayne was saying above. Firefly can’t just happen as an Earth western, and it wouldn’t be the same if it were just a standard issue Star Trek space fantasy either. It requires the elements of the disparate genres to mix.

So why does genre work? Why are we attracted to it? Why do we like playing with it, mixing it and breaking it? Why do some disparage it and others celebrate it? In the post MCU/blockbuster world does it even make sense to think of genres as a convention anymore at all? What are your thoughts? What should we explore here?

So why does genre work? Why are we attracted to it? Why do we like playing with it, mixing it and breaking it? Why do some disparage it and others celebrate it? In the post MCU/blockbuster world does it even make sense to think of genres as a convention anymore at all? What are your thoughts? What should we explore here?

I think that genre is used a lot as a shorthand for marketing, as you said. The problem can be if something is multi-genre and they pick one they can turn off a whole segment who “don’t like” that genre but who might enjoy that work. They might even use it as a springboard into exploring more of that previously-shunned genre. But they never do because they got turned off.

Take one of my favorites, Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander books. Personally I’d call it historical fiction – takes place in (a few) times that are previous to the present and the main characters are not actual people but from time to time they interact with historical people and events.

From Diana’s own website: What Is OUTLANDER?

Frankly, I’ve never been able to describe this book in twenty-five words or less, and neither has anyone else in the twenty years since it was first published. I’ve seen it (and the rest of the series) sold—with evident success—as Literature, Fiction, Historical Fiction, Historical NON-fiction (really. Well, they are very accurate), Science Fiction, Fantasy, Mystery, Romance, Military History (no, honest), Gay and Lesbian Fiction, and…Horror.

My mom who has shelves full of historical fiction – Michener, Follett, Rutherfurd. When I confronted her after discovering Outlander after 5 books had been published asking her how she could have missed it and telling me about it, she said she’d seen it, under Paranormal Romance and featuring time travel. And she doesn’t “do” Paranormal or SciFi.

I think the Dune series could also fall into this category of undefinable.

Perhaps if there was ever an episode where I suspect the conclusion would be, “so we resolved nothing,” this would be it.

I actually taught a class on mystery fiction and the guiding questions of the class focused on how genre functioned: what were the elements necessary to create a mystery story? What happens when it changes? How far can we push against genre until it snaps?

Marketing, or finding keywords to help an audience decide whether or not to give a work a chance, is certainly a functional way to look at genre. But I mostly am interested in how we imagine genre shapes the work itself.

There are multiple ways to theorize genre. For example, if we want to take a page out of the book of Russian formalists like Vladimir Propp (who tried to “scientifically” break down the elements of the folk tale) or the structuralist Tzvetan Todorov (who wrote about mystery fiction), we could approach how we categorize works by what they contain (e.g. a whodunit contains certain plot elements that make it a whodunit). Although some may say that arguing over what elements of a work qualifies it to fit into a genre, I’d say that it shows the stakes of genre studies. To stick with mystery fiction, could we say that Harry Potter (many of the books follow the structure of a whodunit — who broke into Gringotts, who put Harry’s name in the goblet) is a mystery? And if it does qualify as a mystery, what are the stakes of putting it in conversation with “canonized” work like Sherlock Holmes or Agatha Christie? Or, if we read Harry Potter as a mystery, how does that change our point of view?

Genre is also helpful in looking at how we view certain types of work. Although romantic books make a ton of money and, depending on your metric, compromise the largest genre in the market, we don’t really take them seriously anymore. Especially in the academy, why do we valorize someone like Sebald while ignoring E.L. James?

There’s definitely a lot to explore here — excited about the episode!